Five years ago, the state Legislature approved $51 million for two rail shipping centers in the Willamette Valley and eastern Oregon that promised to reduce truck emissions, boost agricultural exports and save farmers money.

Today, the money’s been spent and neither the public, nor farmers, have benefited. The centers, essentially truck-to-rail transfer stations that were supposed to deliver onions, hay and grass seed to seaports in Seattle and Tacoma, and to major cities in the Midwest and the East Coast, sit unoccupied. Not a single truck has been taken off the road, and not a single pound of cargo has been shipped. Two companies that initially agreed to run the depots have both walked, and no one has stepped in to replace them.

Experts warned that the projects could fail. The Willamette Valley depot was not well located, and would struggle to get necessary shipping containers. Key agreements ensuring demand, rates and logistics from both rail centers were not in place.

Nevertheless, the Legislature funded the projects in 2017, with the backing of a state representative who went on to make hundreds of thousands of dollars as a consultant on the projects. The Oregon Transportation Commission, charged with reviewing project proposals, released the state funds in 2021. Since 2017, more than $70 million in public money has been spent or committed to the projects, and the experts’ warnings have been borne out.

In Millersburg, the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center off Interstate 5 promised to move hay and grass seed to ports in Seattle and Tacoma via rail, taking up to 150 semi-trucks off I-5 each day. It was finished in November of 2022 – 10 months late and $10 million over budget – but it sits idle next to the thrumming interstate.

“All I could do is bring them the best information I had available, and they had to make decisions.”

–Greg Smith on Millersburg project

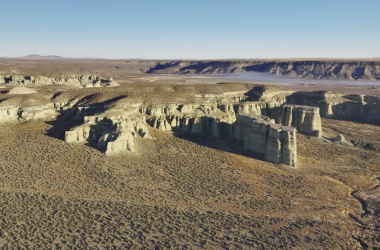

The Treasure Valley Reload Center in Nyssa, which was supposed to save onion growers $2 million per year in transportation costs to Midwest and East Coast cities, has gone $18 million over budget, fallen more than two years behind schedule and is still incomplete, the Malheur Enterprise reported. State officials earlier this year stopped work on the site and are assessing if it is still viable.

Experts told the transportation commission that Millersburg wasn’t far enough from Washington seaports to make rail cost-effective and that it would need the cooperation of two major railroad companies to ensure deliveries and a steady supply of empty containers to transport agricultural goods.

In Nyssa, experts said the railroad would need to move more than just onions to be financially stable, that the volume of produce projected to move through the facility was inflated and that to be successful, Union Pacific would need to commit to an export schedule it was reluctant to offer.

In the end, the facility operators and project managers could not secure all of the necessary agreements and schedules with rail operators. In Millersburg, a lack of containers needed to move agricultural goods continues to keep the facility shuttered.

State Rep. Greg Smith, R-Heppner, urged the Legislature to fund the projects through a state grant program, then economic development groups supported by both Linn and Malheur counties hired Smith to manage the projects.

He told the Capital Chronicle that he knew from the start that the Millersburg facility would face insurmountable challenges. Despite the warnings and years of revised plans, those who backed and built the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center blamed setbacks on one another, as well as volatile market forces and a lack of better information.

“All I could do is bring them the best information I had available, and they had to make decisions,” Smith said of his clients in Linn County.

An Oregon Department of Transportation official blamed the failure to get the facilities running on inexperience.

“These were new facilities, and ODOT does not have and did not have a lot of experience with these kinds of facilities,” said Erik Havig, statewide policy and planning manager at the transportation department. “We did the best we could with the information we had.”

The centers are the first of their kind in Oregon.

Many of the officials who’ve been involved for years with the Willamette Valley project say they’ve learned a lot since it was approved. They insist the project was not a mistake and continue to promise that it will boost agriculture exports and reduce truck emissions.

“We are not happy with how things have gone thus far, but we are determined to put this property to productive use as soon as possible,” Jon Kloor, chair of the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center Board and the Linn County Economic Development Group Board, said in an email. “The basic premise that led to the Department of Transportation supporting this project and a similar project in eastern Oregon remains true today.”

The five transportation commission members who voted to approve the projects did not respond to Capital Chronicle emails or calls requesting an interview. Two commissioners who voted to release funding for the projects continue to serve on the commission today, including its chair, Julie Brown.

There is no plan or timeline for getting either rail center operational. The state transportation department, which distributed the funds to build both, has no practical way to recoup all the money, according to the Malheur Enterprise.

The idea for an intermodal center in the Willamette Valley gained steam in a 2016 report from the Portland-based economic consultancy ECONorthwest. Analysts found that a strategically located truck-to-rail center could help hay and grass-seed growers transport their products to ports in Seattle and Tacoma at rates competitive with truck shipping and take up to 150 semi-trucks per day off I-5. The report noted that moving freight by rail instead of truck reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 75%.

A year later, the Legislature approved $25 million for a Willamette Valley rail center and $26 million for one in eastern Oregon through House Bill 2017, a $5.3 billion package of taxes and fees to fund transportation over the next decade. The bill allocated the money through a grant program called Connect Oregon, overseen by the state transportation department. To receive a Connect Oregon grant, applicants must show that their project can reduce transportation costs for Oregon businesses and connect elements of the state’s transportation system to boost efficiency. In comparison, with $51 million, the state could have invested in more than 120 electric buses or 1,200 rapid charging stations for electric vehicles, based on average prices from the U.S. Department of Energy and the West Coast Electric Highway.

Twelve of the 14 members of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Transportation Preservation and Modernization, including Smith, supported the state’s investment in the projects.

Soon after the Legislature approved the funding, Linn and Malheur counties contracted Smith and his consultancy, Gregory Smith & Company, to help their nonprofit economic development groups pitch projects for those Connect Oregon grants. Smith was already working as Malheur County’s economic development director during the time he advocated funding the projects at the Capitol. The county paid Smith an additional $6,000 per month to manage the Treasure Valley Reload Center project.

According to the Oregon Government Ethics Commission and Oregon law, Smith did not violate any laws by working as an elected official to direct state money to projects he was eventually hired to manage as a private consultant.

A location problem

The Oregon Transportation Commission, which sets state transportation policy, was responsible for vetting plans for the projects. From 2017 to 2021, its members heard from a variety of rail and freight experts who repeatedly said the Mid-Willamette Valley project would only work if it fulfilled key requirements. Among the earliest requirements was securing the cooperation of two railroad giants – Union Pacific and BNSF – which control different sections of track needed to move goods from Millersburg to Seattle and Tacoma. Both railroads would also be needed to get a steady stream of empty containers from Chicago, Kansas City, Denver, Salt Lake City and coastal ports to Millersburg.

In the final proposal for the Mid-Willamette Valley facility, Keith Leavitt, chief trade and economic development officer for Port of Portland, wrote:

“The active participation and cooperation of both Class I railroads (Union Pacific and BNSF) is equally critical to the success of the Mid-Valley Intermodal Facility as both railroads control different segments of the mainline between the Valley and Seattle. The railroads will need to provide heavy-haul rail cars capable of handling the agricultural export loads that are generated out of the Valley from the facility.”

By the time the Mid-Willamette Valley facility was approved, only Union Pacific was signed on to run trains through the facility, and there was no certainty the company would be able to get empty containers from the Midwest or the coast to Millersburg. Any mention of BNSF as a partner was eventually dropped from the project following its approval by the commission.

Despite Union Pacific getting exclusive access to the publicly funded rail project, the rate and track agreements between the company and the operators at the Mid-Willamette Valley center are confidential, according to the state transportation department.

The center also faced a location problem, as the California-based freight consultancy Tioga Group noted in an analysis in 2019 for the commission. Rail is usually only cost-effective when goods are transported 500 or more miles, according to supply chain experts. Millersburg and Seattle are 230 miles apart. That meant that trucks would remain a cheaper option for Willamette Valley farmers, the analysis said. Smith, who had helped pitch and refine the plans for Millersburg from late 2017 to the summer of 2019, said this was a concern he had flagged to the project’s supporters in Linn County.

“I knew that the distance issue between Millersburg and (Seattle and Tacoma), economically, was going to be very, very hard to overcome,” he told the Capital Chronicle. “After that, I mean, I didn’t have anything to do with the design, I didn’t have anything to do with the negotiations or contracts.”

John Pascone, president of the economic development group in Linn County, refuted Smith’s claim that he had expressed concerns about the location.

“Greg Smith was always high on the project and to my knowledge never expressed any doubts about its viability,” Pascone said in an email to the Capital Chronicle. “He was an energetic and supportive project manager during his involvement.”

Smith’s work with the county officially ended in July, 2019. He pocketed between $150,000 and $200,000, according to Pascone, and his contract was not renewed. Kloor, of the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center Board, would not comment on cutting ties with Smith, while Smith said he chose to leave the Millersburg project to dedicate more time to the one in Nyssa.

‘Necessary milestones’

In January 2021, the director of the Oregon Department of Transportation, Kris Strickler, recommended that the commission release the necessary funds to finish building the projects.

“At present, both project sponsors have submitted to the department documentation that demonstrates that they have met all of the necessary milestones,” Strickler wrote.

A day later, two Tioga group analysts wrote a “confidential memorandum” to John Boren, the manager of the department’s freight program, saying again that the Willamette Valley project lacked critical components for success.

“It appears that successful operation of the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center terminal and intermodal rail service between Millersburg and the ports of Seattle and Tacoma depends on a series of assumptions that have yet been verified,” said Daniel Smith and Frank Harder. “Project success thus rests on factors that are still unresolved.”

That warning did not dissuade the commission from moving forward, according to Havig of the transportation department.

“We don’t remember anything from Tioga saying: ‘This project or any of these projects are going to completely fail,’” Havig said.

Kevin Glenn, the department’s communications director, told the Capital Chronicle that the Tioga analysts were merely highlighting challenges each facility would face and how best to address those challenges.

“They never stated that if these challenges were addressed that the facility would absolutely be successful, nor that if these challenges were not completely addressed that the proposed facility would absolutely fail,” he wrote in an email.

The transportation department had over the years reimbursed the project developers periodically for money spent, but on Jan. 21, 2021, the commission agreed to release what was left of the $51 million to build the centers.

Construction on the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center took 10 months longer than anticipated and cost $10 million more than the $25 million initially approved. Linn County leaders attribute this to inflation and delays caused by COVID and used federal COVID relief dollars to pay the difference. To pay for maintenance, operations and fees on the land and buildings, Linn County leaders have used nearly $2 million from its annual economic development money from the state lottery.

Every warning about the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center remains valid today. There is no guaranteed supply of shipping containers. The railroad is still at a distance from seaports that makes truck shipment less costly, and the facility does not have agreements to move any Willamette Valley produce.

Two companies hired to operate each of the rail centers, including managing negotiations with the railroads, the shipping container suppliers and area agricultural producers, dropped out of their contracts to run the facilities in 2023, and no one else has stepped in to replace them.

Both the Willamette Valley and Treasure Valley projects don’t make economic sense, critics say. Yet no one appears to have accepted responsibility for the projects running over budget and failing to function.

The consultants who promoted the projects have been paid. So have most of the developers. The Malheur County Development Corporation, the Linn County Economic Development Group and the board of the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center are responsible for ensuring the projects are finished and functional one day.

Linn County commissioners did not respond to a question about why they continued to support the Mid-Willamette Valley project and the economic development group, despite the projects’ red flags and the extra costs, or what they plan to do now.

“That question might best be answered by the Mid-Willamette Valley Intermodal Center board of directors, but we believe this is a valuable long-term asset for the mid-valley and it will take time to roll up,” spokesman Alex Paul said in an email on behalf of the commissioners.

The intermodal board’s chair referred questions about why the project continued to move forward and receive funding despite the warnings to the county and the state.

“We believe Linn County and the Oregon Transportation Commission are the appropriate parties to respond to this question,” Kloor, the board chair, said in an email. “That said, we believe it is way too early to declare this project a failure.”

Officials with the state’s transportation department and the transportation commission take some responsibility.

“The ultimate decision to move forward and to construct the facility was with the (transportation) commission,” Havig of the transportation department said of the Willamette Valley center. “But I would also point out that there were clear expectations in House Bill 2017 and from the Legislature that this was a project that was strongly supported. So there was a lot of political support behind it as well.”

Smith, who is in the unique position of bearing at least partial responsibility for the projects at the legislative level and orchestrating the financing of the projects in both counties, only acknowledges responsibility for some mistakes at the Nyssa center.

His consultancy took in $15,000 a month from 2018 to 2022 for economic development work in Malheur County and for managing the Treasure Valley Project. He said if he could do it over again, he would have characterized the $26 million budget he pitched for the center as “seed money,” rather than the full cost. He abruptly resigned from his work with Malheur County last February, right before the county’s third request to the Legislature for financial help to finish the project.

Smith said he bears no responsibility for promoting a flawed plan in Millersburg.

“That was all managed by a board. It was all managed by elected officials,” he said. “I had no decision making in Millersburg. Zero.”

Oregon Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oregon Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact [email protected]. Follow Oregon Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.