Five years ago, Malheur County got big economic news – the Treasure Valley Reload Center was moving ahead.

On Sept. 27, 2018, the Malheur County Development Corp. delivered to the state a 134-page plan.

Page by page, it brimmed with optimism, starting on the first page with a statement from Grant Kitamura.

Kitamura, a veteran onion industry executive in Ontario, had taken on the role as president of the development company.

“The project plan before you will deliver on the efficient movement of commodities, transportation cost savings, and public and private benefits,” Kitamura wrote.

Onions would move out of Nyssa by fall 2020, the plan said.

Oregon’s highways would be safer, residents would breathe less polluted air, and new jobs would bloom.

None of that has happened.

Instead, after millions spent, the project is at a dead stop.

Yet another promised opening date come and go unfulfilled.

A new project manager – Shawna Peterson – is taking a fresh look at what to do with partially-finished rail lines, a steel building sitting on the ground in pieces, and disturbed ground sprouting weeds.

That wasn’t the work she expected when she signed on last March. The Ontario lawyer, well connected and known as an effective organizer, was tasked to oversee finishing touches on the reload center. She took over tasks left undone by Greg Smith, a Heppner consultant and state legislator who quit with little notice.

“We really need to stand up something that’s going to be good for the county in the very long term.”

–Shawna Peterson, executive director, Malheur County Development Corp.

Peterson hopes to restore the community’s optimism for a project tainted by politics, incompetence and runaway costs.

“Everybody’s weary, myself included,” Peterson said in an interview. “I hope that people are encouraged that even if there’s frustration about how we’ve gotten to this point, the lessons learned aren’t going to be wasted by me.”

She stopped construction, with the development board’s approval. Now, she is focused on crafting a new vision for the Treasure Valley Reload Center.

“We really need to stand up something that’s going to be good for the county in the very long term and this is an opportunity to do that,” Peterson said.

To do so, Peterson needs to build a new business plan.

The one advanced five years ago is stale – and built on bad assumptions, a review by the Enterprise found.

The project was sold to the state and the community as bringing a string of benefits.

Project leaders said operating from Nyssa would mean 4,200 truckloads of onions would no longer need to make the 200-mile trek to Washington state.

That would cut wear and tear on Oregon highways that the public has to fix, the plan said.

That would reduce deaths from collisions, particularly on a “treacherous” stretch of Interstate 84 east of Pendleton.

And that would cut shipping costs for the onion industry by nearly $2 million a year.

Those advantages all added up to benefits for Oregonians that warranted public spending on the rail depot.

But those claims were built on a fiction. Nowhere near 4,000-plus onion trucks were heading to Wallula, Wash. At most, say former managers of the Washington depot, the Treasure Valley sent maybe 400 trucks. And some of those came because the Wallula shipping center promised cut-rate trucking – or even free.

Kitamura said 4,000-plus trucks loaded with onions do leave the area – but they are mostly headed to East Coast destinations.

That means they get out of Oregon in a dozen miles or so, not the 200-plus trek project organizers had cited.

But Malheur County officials and those at the Oregon Department of Transportation didn’t question the numbers.

Instead, the state opened the door to $25.6 million.

That sum was set aside by the 2017 Legislature in a deal engineered by Cliff Bentz, then a state representative from Ontario and now a congressman.

Kitamura said that in fact was the start of the troubles. He said looking back, it seems insensible to name a number and then design a rail depot. The order was backwards.

Project officials acknowledged as much in that 2018 master plan. Buried deep in its pages was a listing of elements already dropped as unaffordable – including widening state highways outside Nyssa to safely handled the extra truck traffic.

But the development company forged ahead, aiming to have the rail center done by 2020.

In the coming years, problem piled atop problem.

Regulators rejected requests for permits to build across wetlands, saying essential information was missing.

Closing a deal with a company to run the depot took months, in part because the company – Americold of Georgia – had trouble pinning down just how committed was the onion industry to this public depot.

A key claim made to the state in 2018 proved wildly wrong.

“The wetlands present on the site will not hinder the proposed development of the reload facility,” the development company said in its plan.

When construction finally started, it stalled quickly as crews encountered mud and muck far deeper than engineers figured. They spent weeks hauling tons and tons of rock to patch the holes, running up millions in unexpected bills that drained the project budget.

The development company board, appointed by the Malheur County Court, rarely got budget reports. Over time, five of the original eight members quit.

A closer watch on the finances would have shown a project mired not only in mud but in debt. Smith, the project leader, vowed to the board not a dollar would be spent that wasn’t in hand. In fact, the company was plunging deeper into debt, borrowing from a bank to pay bills and eventually just telling vendors they would have to wait for their money.

As it became clear the project was off the tracks, the board and county commissioners asked Smith few substantive questions. They agreed to his insistence in June 2022 that his consulting fee be boosted from $6,000 to $9,000 a month – paid out of the county treasury.

But matters only worsened.

In April 2022, Smith told the board his team was dropping plans for one of four rail spurs. There wasn’t money to build it, he said. Six months later, his team said Union Pacific Railroad required the rail spur – or Nyssa wouldn’t get the expected service. That was no surprise to Smith’s team. The original operating plan for Treasure Valley Reload Center told of the need for all four rail spurs.

Faced with a surprise cost, county commissioners ponied up $2 million to cover the foul-up.

Along the way, project leaders kept going back to the state for more money as well. State Sen. Lynn Findley, the Vale Republican, pleaded with colleagues with an emergency $3 million grant in late 2022. He assured them that would get the project done.

Instead, project leaders stunned development company directors and county officials with new calculations that Treasure Valley Reload Center would need not $3 million but another $10.5 million.

As questions and costs mounted, Smith quit his role with the development company in February 2023.

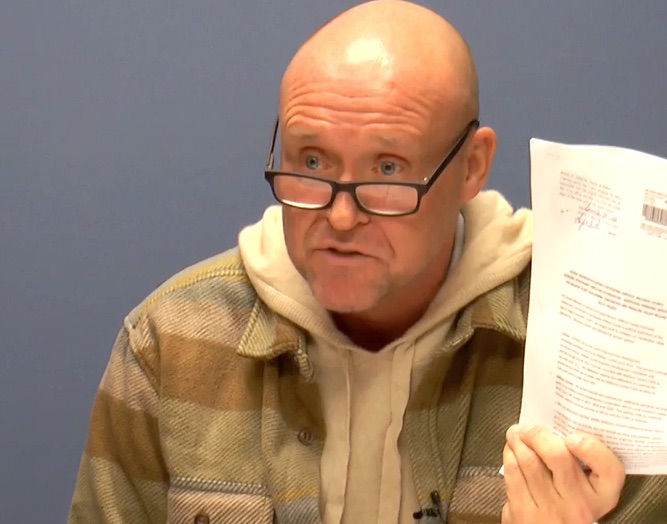

Development company officials then brought in Peterson.

A local attorney, Peterson had won high marks in the community and with state officials for her work with the Eastern Oregon Border Economic Development Board. The board awarded local grants to boost economic development, using a careful and public process.

Peterson turned her penchant for organization to the disarray in Nyssa. She understood her main tasks – keep construction going, round up some more money, rebuild community trust in the project and get the reload center functioning.

She brought in outside experts to vet construction costs and needs. She worked to figure out what had been spent, what was still needed, and what money was left in the project kitty.

Peterson, by now a veteran of legislative politics, knew she had to present a strong case for yet another round of state founding. Just as she was to submit her report, Peterson found her figures were off – about $1 million in unpaid bills was lurking that she hadn’t been told about.

The bad news accelerated through the summer.

The application turned in by engineers to get a building permit to start the warehouse was deeply flawed. Work scheduled to start in May had to wait.

In July, Americold backed out. The development company now had no one to run its Nyssa center.

The Oregon Department of Transportation soon followed with notice it was freezing $8 million it was holding for the project. The agency questioned whether Treasure Valley Reload Center any longer made sense.

And in September, engineers reported that Union Pacific Railroad was now questioning how more than three miles of track had been built. That raised the specter of rebuilding every mile at huge expense.

Through it all, Peterson responded with a practiced coolness.

Now, she said, it’s time to consider a new game plan.

In an interview, she outlined where she is heading to revive the project.

Her first step, she said, is to determine what the reload center could be used for. Onions will remain part of the mix, she said.

She wonders, though, about all the trucks hauling freight to the massive warehouses lining Interstate 84 between Ontario and Boise. She wants to find out if that freight could instead go by less-costly rail to Nyssa and then be trucked for a shorter distance to the warehouses.

She said that in-bound freight “is a promising business plan angle.”

She also wants to assess the range of what’s grown or made in the area that could go out by rail.

Peterson said she’s likely going to need outside professionals to help her assess the market for a new rail center.

Meantime, she’s scouting for a company to replace Americold. A new operator could help plot a new future for the Nyssa project, Peterson said.

After that, the existing design of Treasure Valley Reload Center has to be assessed. Changes in buildings might be needed to serve newly-identified customers.

Kitamura supports that course.

“It may not be a pass-through with raw products,” he said. “It may be containers. You just need a pad and a crane to load containers. You may not need a building.”

And then comes the task of figuring out the new cost to complete the reload center.

All of that would have to be folded into a new business plan aimed at a key audience – executives at the Oregon Department of Transportation.

They have signaled that they face a decision themselves to back the project longer or to call it done and find a way to recover the $25 million in state money sunk into Nyssa.

Peterson realizes the stakes, saying, “It would basically be whether they have to go nuclear and say ‘What can we recoup?’ versus ‘What can we make out of this project in a new and improved way?”

Peterson said she hopes to have the right answers by February.

NEWS TIP? Send an email to [email protected].

SUPPORT OUR WORK – The Malheur Enterprise delivers quality local journalism – fair and accurate. You can read it any hour, any day with a digital subscription. Read it on your phone, your Tablet, your home computer. Click subscribe – $7.50 a month.