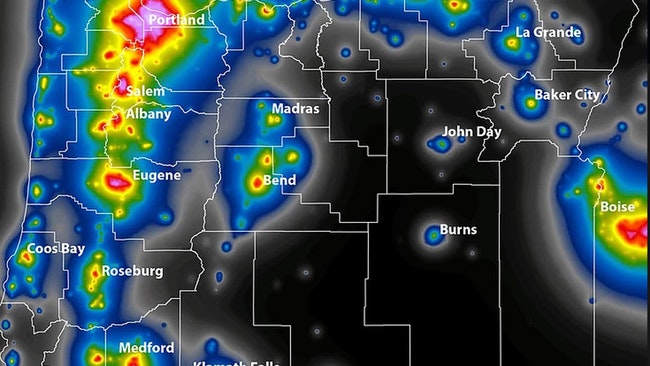

A map shows a broad expanse of southeast Oregon where the dearth of light pollution makes dark, star-lit night sky possible. The bright splotches show the relative brightness detected in and around population centers. (International Dark Sky Association)

Known for its fertile fields, vast rangelands and rugged scenery, Malheur County has another critical resource that’s rapidly diminishing across the globe – a night sky relatively free from artificial light.

That loss of dark sky elsewhere has sparked a movement to celebrate and preserve the remaining dark sky areas.

In Oregon, advocates are focusing on the remote territory known as the Oregon Outback and have organized as the Outback Dark Sky Network. Their goal is to nominate a swath of Lake, Harney and Malheur counties as the Oregon Outback Dark Sky Sanctuary through the International Dark Sky Association’s dark sky places program.

“We’re unique,” said Dawn Nilson, a natural resources manager and International Dark Sky Association delegate in Oregon. “This would be the largest dark sky place in the world, and it’s located in the largest contiguous area of pristine sky in the continental U.S.”

In places like Malheur County, people may take the dark skies for granted. They can step outside almost any night to view star-studded skies, on the open range or even in the back yard.

That’s not true in many – perhaps most – places.

“A recent study estimates that global light pollution has increased by 49% over the last 25 years, and even up to 270% if you factor in the lights that aren’t seen by satellites,” Nilson said. “More than 80 percent of North Americans can’t see the Milky Way from their homes.”

That underscores the importance of preserving special places like the Outback, she said.

The sanctuary proposal has been in the works since 2018, with a steering committee of citizens, land management agencies and local officials meeting regularly. She said local participation is a critical component.

“This is grassroots, and we want it that way,” said Nilson.

The nomination prep work has included taking sky brightness measurements of the night, conducting lighting inventories, establishing a sanctuary boundary, building support and programming – all required to support the proposal to the international association.

The nonprofit association has certified nearly 200 sanctuaries around the globe since its founding in 1988.

Nilson said the Outback plan envisions certification in phases, starting with about 3.7 million acres in Lake County and a portion of Harney County, where local officials and other stakeholders have been engaged in the plan the longest.

Nilson said the next phase would expand the sanctuary farther into Harney County. Malheur County would be the third phase.

When complete, the sanctuary could span more than 11 million acres, making it the largest dark sky sanctuary in the world.

By comparison, the largest designated dark sky place in the world today is Death Valley National Park, at 3.1 million acres.

The trouble with light

The stars have been important to humans for light, navigation, mythology and more since the beginning, Nilson noted.

“We are hard-wired to be attracted to twinkly lights, to the stars,” she said.

Equally important is the age-old cycle of day and night.

However, when artificial light changes the equation, “it disrupts the hormonal clocks of beings that live above the ground. Every day needs a night,” she said.

With natural night skies losing out to artificially lighted areas, scientists are documenting bird deaths and negative impacts on animal migration, mating and foraging.

Nilson said recent surveys associated brighter residential night lighting with sleep problems, impaired daytime functioning and obesity. In 2016, the American Medical Association encouraged communities to minimize and control blue-rich environmental lighting by using the lowest emission of blue light possible to reduce glare.

Nilson noted that communities and large metropolitan areas in particular cast light well beyond their boundaries. On the northeastern edges of Malheur County, once-pristine night skies already are dimmed by a growing artificial light-shed she refers to as “the Boise Bubble.”

Creating a sanctuary won’t immediately reverse that, she said, but it would raise awareness of ways to curb the trend, and help protect as-yet unmarred dark sky areas.

A graphic produced for Dark Sky Week in 2021 shows impacts of different lighting styles on night sky visibility, and encourages use of tools to minimize light pollution. (International Dark Sky Association)

A graphic produced for Dark Sky Week in 2021 shows impacts of different lighting styles on night sky visibility, and encourages use of tools to minimize light pollution. (International Dark Sky Association)

The certification effort

Nilson stressed that certification as a dark sky sanctuary doesn’t mean regulations or mandates.

The international association sets rigorous standards for dark sky certifications, but if these aren’t met within a certain timeframe, the worst that can happen is the site loses its designation.

It’s a recognition program to foster awareness of the special nature and increasing rarity of dark sky places, and to spur educational outreach about the types of lighting that cut back on light pollution.

Nilson said people living in those dark areas can be safe and productive stewards of the land – while still protecting their dark skies.

“We’re not saying everybody needs to turn off the lights. This is about dark skies, not dark ground,” she said. “We’re just saying, think about the lights you have and ask if they are really necessary. If the answer is yes, ask how you can make them dark sky-friendly.”

She said of all the pollutants today, light pollution is probably the easiest to minimize.

A simple rule of thumb, she said, is “Don’t put a light on if you don’t need it, and shield it when you do.”

Too many light fixtures direct light skyward, she said.

“It’s wasted light. We don’t need to light up space, we need to light up the ground,” she said.

Shielding can direct light where it’s needed. Other choices that are dark sky-friendly, she said, call for warmer yellowish light, not the blue-rich white light, and motion- or timer-triggered, rather than dusk to dawn lighting.

An important aim of the project is to give those living and working in dark sky areas information about lighting choices and their impacts.

“This is all voluntary. This is not regulatory,” she said.

She stressed that the sanctuary concept is about preserving what’s there now.

“It’s a celebration of the dark skies we have,” she said. “And awareness creates further protection.”

Potential benefits

One benefit of certification is that it could attract funding to retrofit or install energy-efficient and dark sky-friendly lighting.

“This could open the door for grants,” Nilson said. “This benefit has occurred near and at other certified dark sky places.”

She said sustainable tourism also could see a boost. While visitation within the sanctuary would be dispersed throughout the Outback, those drawn to the area would likely use local communities as jump-off points.

Cities generally don’t have the level of darkness to be included in a sanctuary, but they play an important role – and stand to benefit economically – as gateway communities, she said. Visitors stop in these towns to stay overnight, buy gas and provisions, and visit museums and view other attractions while they are in the area.

Noting that some rural residents are leery about tourism, Nilson cautioned that this type of tourism doesn’t attract “millions of people,” thanks to the remoteness and solitary appeal of Outback recreation.

Next steps

The Outback Dark Sky Network hopes to submit the Lake County phase in the spring for certification by the end of the year.

“We want to get at least a portion of it certified this year,” she said.

With a backlog of nominations, the international organization may take several months to review the Oregon Outback plan.

Meantime, the group continues to meet online, conduct lighting inventories and grow the network.

People interested in learning more can go to the Oregon Outback Dark Sky Network on Facebook to find a web link to sign up as a supporter and receive email updates.

Star-struck? Check this out …

Friends of the Owyhee, a partner in the dark sky effort, is doing a series of webinars about the Oregon Outback. On Wednesday March 16, Sammy Castonguay, Treasure Valley Community College astronomy instructor, will continue his series “Stargazing and Natural Night Skies.” To register, visit Friends of the Owyhee on Facebook.