CORRECTION: A review of this story after publication identified factual errors and flaws in data analysis. To learn about the errors, please see this POST.

Editor’s Note: This Nov. 14 story by the Malheur Enterprise and ProPublica was based on data provided by Oregon’s Psychiatric Security Review Board that turned out to be incomplete. The board, in response to a series of public records requests, turned over the names of 334 people it said it had released from 2008 to 2017. After publication, the board informed the Enterprise that it had actually freed 526 people found not guilty by reason of insanity for felonies during those years. The updated story with the analysis of what happened to all 526 people after release can be read here.

About 35 percent of people found criminally insane in Oregon and then let out of supervised psychiatric treatment were charged with new crimes within three years of being freed by state officials, according to a comprehensive new analysis by ProPublica and the Malheur Enterprise.

The analysis and interviews show that Oregon releases people found not guilty by reason of insanity from supervision and treatment more quickly than nearly every other state in the nation. The speed at which the state releases the criminally insane from custody is driven by both Oregon’s unique-in-the-nation law and state officials’ expansive interpretation of applicable federal court rulings.

In Oregon, those decisions are made by the Psychiatric Security Review Board. The five-member panel of mental health and probation experts has custody of defendants found not guilty by reason of insanity and oversees their treatment.

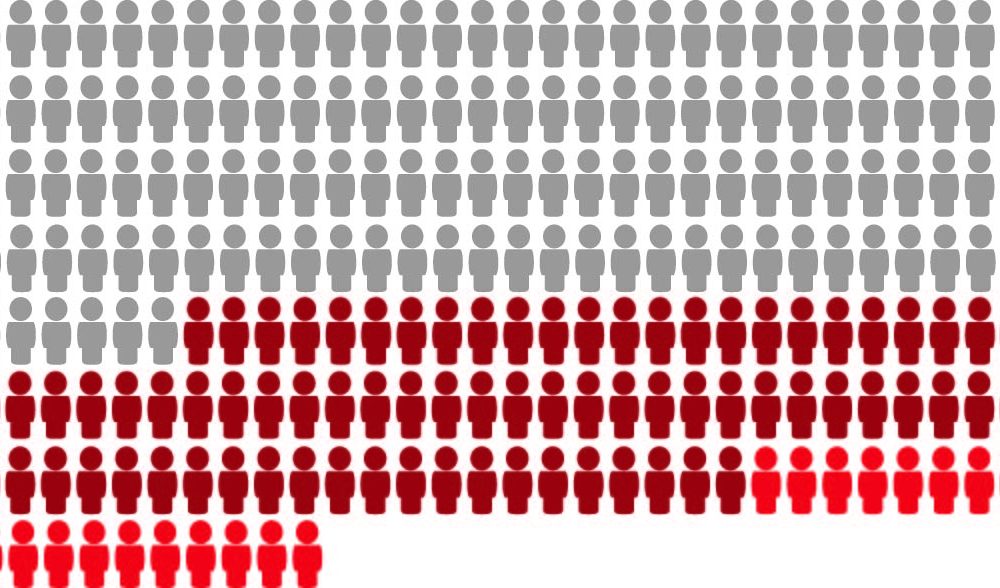

Between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 15, 2015, the state freed 220 defendants who had been acquitted of felonies because they could not tell right from wrong or control their actions. About a quarter of them, or 51 people, were charged with attacking others within three years. Twenty-five were charged with lesser crimes. (Those 76 people are shown above in dark red.) Eighteen others were charged more than three years later, including 12 people for violent incidents. (They are shown above in light red.)

They were charged with felonies about as often as people freed after serving prison terms — both 16 percent — according to our analysis and the Oregon Department of Corrections.

The frequency of new crimes and violence startled experts who have long hailed Oregon as a leader in balancing the civil rights of patients against the need to protect the community. Many mistakenly believed that only a tiny percentage of the people released by state officials went on to commit new crimes.

“I didn’t know that,” said Dr. Landy Sparr, who directs the Forensic Psychiatry Training Program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland and has evaluated hundreds of insanity defendants in the state. “I’m totally surprised.”

One reason for Sparr’s misimpression was that the Psychiatric Security Review Board has not publicly disclosed what it has learned about this issue.

On its website, the board assures Oregonians that repeat offenses by people it supervises are exceedingly rare events, with only 0.46 percent of defendants committing new crimes each year.

That rosy statistic does not encompass the significant problem of what happens after defendants are freed, and the board knows it. Almost three years ago, internal documents show, board officials exchanged emails about the rate of crimes committed by clients released from oversight. The officials launched a preliminary study of three sample years, which found from one-third to one-half of the people freed by the board had since been arrested on new charges. They limited that search to Oregon records, which means the real number of crimes is almost certainly larger.

Those numbers are “higher than I was expecting given how well our clients do on supervision,’’ Juliet Britton, the board’s former executive director, wrote in a September 2017 email.

The board’s study of what happens to people it frees was never shared with the public. Nor was it provided to the governor, who appoints the board; the legislature, which oversees its budget; or the treatment providers who work with its clients, according to available records. They now say they never shared its figures because the study wasn’t finished and it wasn’t peer reviewed, the process in which academic journals enlist independent scholars to review a researcher’s findings before publication.

The agency’s calculations were described in internal emails obtained through a public records request. Board officials did not acknowledge the existence of the figures in interviews for this story. Instead, they questioned the methodology and ethics of the Enterprise-ProPublica analysis, even though it paralleled what the board had already done.

Executive Director Alison Bort declined to answer eight written questions about the board’s internal study and its public statements about recidivism. She said in an email that the inquiries were “loaded and conclusive that our agency has been intentionally dishonest.” (Read this timeline to see the questions, the board’s public comments and internal emails since 2016.)

Bort said the agency is concerned about the frequency of new crimes committed by people it frees. She defended the decision not to share the recidivism figures with the public, saying they had “not been statistically analyzed.” “It would not only be irresponsible (and for me as a licensed psychologist, unethical), but potentially harmful for the agency (or any entity) to share with the public at its current stage,” she wrote.

Bort said the agency is not currently working on the study. She said officials may resume the research next year if the legislature does not give the board additional duties that “would take precedence.’’

For now, the Enterprise-ProPublica analysis offers the only public accounting of what happened to people the board has released in recent years. We obtained the names of every person the board freed and searched criminal records available in Oregon and across the country.

In many cases, we found, insanity defendants returned to abusing drugs, damaging property or hurting themselves or others. In the most extreme cases, they raped or killed.

Among those harmed were relatives caring for them without adequate support and police officers called to confront deeply distressed people.

We began investigating the state’s system for the criminally insane after Anthony Montwheeler, a man who had long lived along the Oregon-Idaho border, was charged with two murders just weeks after the board released him.

Montwheeler’s case was extreme but not unusual.

There was Timothy Ashmus, a man from a coastal Oregon town who was found not guilty by reason of insanity in a December 2010 burglary, mischief and theft case.

Within five months of his sentencing, the Psychiatric Security Review Board decided he was no longer mentally ill and freed him. Seven months later, Ashmus got high on meth, strangled his 8-year-old relative and then threw a toddler across the room. He was sentenced to probation for criminal mistreatment and strangulation. He accrued other minor charges until, about two years later, he was sent to prison for raping a woman who had came by his house to give him a ride to a karaoke night with friends. In a letter to the Enterprise, Ashmus denied the rape and said he had been wrongly convicted.

Dung Phan, a Portland man, was freed from the board’s supervision in 2014 after being found criminally insane in a 1997 arson, mischief and trespassing case. Within weeks, he was charged with assault, but the case was dropped. About a year later, he threw a flaming newspaper at the back of a Korean tourist, which quickly burned a hole through her down coat. Phan told police he was “the next Hitler”; doctors said he was suffering from schizophrenic delusions. Authorities charged him with arson, intimidation, attempted assault and reckless endangerment. He apologized in court and pleaded insanity. A judge agreed and returned him to the oversight of the Psychiatric Security Review Board.

A divided board voted to release Anthony Aldeguer in 2011 after he had spent more than three years in the state’s care. A Polk County judge had found Aldeguer legally insane in 2007 after he attacked two police officers who were attempting to arrest him for making meth. Almost two years after being freed, he was charged with possession of meth and cocaine, but the case was dismissed for insufficient evidence. In 2015, he pled guilty to another possession charge while homeless. Later that year, he fired shots at two men who were pulling their raft from the Yamhill River near Bellevue. He pleaded guilty to menacing and reckless endangerment, among other charges, and was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

The Enterprise mailed letters to the last known address of every person in this story who had been found criminally insane. Most were returned undeliverable. When phone numbers could be found, a reporter also tried calling. Ashmus was the only person to respond.

Most states are reluctant to end oversight of people like Ashmus, Phan and Aldeguer until they show that they can manage their illnesses on their own and are not a danger to others. Many states supervise the care of such defendants for decades longer than Oregon and rarely, if ever, end all oversight.

Oregon is different because of both legal restrictions and the approach of state officials who make the decisions.

Experts also said the Enterprise-ProPublica review illustrates deeper failings in the state’s treatment of people with mental illness, which is often a lifelong chronic condition. The defendants freed by the board could well be stable the day they leave state custody. But without access to health care, housing, employment counseling, a positive social network and a caseworker to help them navigate a social safety net, they can be a substantial danger.

“It’s very expensive to provide all of that. There isn’t enough of that for people who have the need,” said Larry Fitch, the retired state director of forensic services and mental health in Maryland. “If you’re in the community and you’re not under a court order that leverages all these resources for you, you get what you personally can manage to leverage and it’s rarely going to be optimal.”

Bort said the board was doing all it could to protect the public, given the limits imposed by state and federal law. She said the number of serious, violent crimes the Enterprise-ProPublica review documented was “concerning, of course,” but “that’s different from our responsibility.”

Board members have declined repeated interview requests but said in a joint response to written questions that the 11-person agency has “limited resources.” The governor appoints five people to serve on the board part time: a psychiatrist, a psychologist, an attorney, a probation or parole officer, and a public member. The executive director oversees a small staff that facilitates more than 1,000 hearings each year and coordinates with treatment providers.

“While any recidivism by any former client is concerning, our agency’s responsibility is to the clients under our jurisdiction,” they wrote.

Britton, the board’s former director, took the opposite view, arguing that the board has a responsibility to track what happened to former clients.

In a 2016 email about the plans to conduct a detailed study of recidivism, Britton and a staff analyst told state police she needed data on arrests of released clients “to carry out PSRB’s legislative responsibilities.”

Britton, in an email this month to The Enterprise, wrote that she left the agency while the study was still in the planning phase and that additional statistical analysis and outside review had to be done before it could be released. ““Despite having the primary duties related to operating a highly complex state agency, staff, including myself, dedicated weekends and evenings to these special projects in an effort to shed light on the forensic mental health system.”

State law does not require the board to track outcomes of their decisions to free people. But Britton said in emails that she believed board nonetheless needed that information to improve decisions and guide policy reforms.

Susan Harmon agrees.

She believes her daughter, one of Montwheeler’s ex-wives, would be alive if the board had taken a less legalistic approach to its duties and listened to doctors who warned that Montwheeler was likely to attack family or friends.

Instead, board members unanimously voted to free him. He is now charged in connection with the deaths of Annita Harmon and David Bates, whose car he hit during a police chase.

“They should be held accountable,” Harmon said of the board.

How We Got Here

In the 1960s, the United States moved away from warehousing people with mental illness, both because of the costs and a growing civil rights movement.

Congress offered states financial incentives to expand mental health care within local communities. Oregon was the first in the nation to extend this approach to people deemed criminally insane.

In 1971, Oregon overhauled laws governing insanity defendants, moving many patients out of the Oregon State Hospital into supervised community treatment. Dozens of states have since adopted similar practices for insanity defendants. About 30 states routinely release all but the most ill or dangerous defendants from secure psychiatric hospitals, sending them to less restrictive environments where doctors can keep a close eye on their mental health. Studies show this helps patients gain the ability to live on their own while protecting the public.

Oregon’s strategy stood out in two ways.

In 1978, legislators created the Psychiatric Security Review Board, making Oregon one of only three states where a professional board, not a judge, manages custody of the criminally insane. The others are Connecticut and Arizona, where far fewer people successfully plead insanity.

Forensic psychiatry experts argue that Oregon’s system more effectively protects defendants’ rights because judges, who are often elected, overly worry about the political risks of freeing people from supervision. States that rely on judges, they say, tend to lock the criminally insane in costly, secure facilities long after they are well enough to be set free.

Oregon also is one of only five states where, by law, the state must end its oversight of people found not guilty by reason of insanity at the moment they would have completed the maximum prison sentence had they been convicted of a crime.

This sets Oregon apart. Most states free people only after doctors conclude they can live on their own without posing a danger to themselves or others. The doctors must persuade a judge their conclusion is sound. Oregon requires no such assessment when a defendant’s time is up. It just opens the door.

A review of hundreds of cases shows that when Oregon officials make those decisions, they interpret federal court rulings differently from their colleagues in other states, putting greater weight on individuals’ rights to freedom. Other states take a narrower view of the same decisions, putting more emphasis on protecting the community.

Bob Joondeph, the longtime leader of Disability Rights Oregon, defended the state’s approach as fundamentally fair to people with mental illness.

“If you think somebody is a bad actor, should we hold on to them for the rest of their lives?” he asked.

He said the answer in other states is often influenced by prejudices against people with mental illness, even though researchers have not directly linked those conditions to violence. He noted that even in Oregon, most people who plead insanity remain under state supervision longer than if they had served a prison sentence.

(One reason for that statistic is that defendants who plead guilty to crimes or are convicted rarely receive the longest possible prison sentence. The Enterprise-ProPublica study found that about half of the people who plead insanity end up being supervised for the maximum possible period.)

Today, Oregon monitors about 500 people sent to treatment instead of prison because active symptoms of a mental disorder, like schizophrenia or a developmental disability, made it impossible for them to follow the law.

The process begins when a judge or jury rules that a person charged with a crime is “guilty except for insanity.’’ Despite the apparent meaning of those words, the finding is legally equivalent to “not guilty.’’ Typically, people start their care at the state mental hospital. If they make progress, doctors ask the Psychiatric Security Review Board for permission to move them into community treatment, which ranges from a secured facility to a group home, supported housing or even independent living. At each step along the way, they remain in the custody of the board, with state officials deciding how much freedom they can be allowed.

Two-thirds of Oregonians who pleaded insanity live in the community while being monitored by state officials, going to therapy, attending support groups and working. If they violate terms of conditional release, the board can have them arrested and return them to the state hospital.

The board can decide to discharge patients early for two reasons: If they are no longer a danger to the public or if they are no longer affected by one of the qualifying mental disorders spelled out in law. These include schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but not personality disorders, substance use or sexual behaviors such as pedophilia. The legislature and state appeals courts have repeatedly narrowed the legal definition of the mental illnesses that qualify for an insanity defense, requiring the board to free people courts had found criminally insane under the previous rules.

Bort, who treated people found legally insane as a psychologist before becoming director of the board, said the decisions can be difficult.

“We’re trying to balance a person’s civil rights with the law, with the dangerousness,” she said.

The text of Oregon’s law sets a seemingly clear standard for what should take precedence. It says, “the board shall have as its primary concern the protection of society.”

Harmful and Harmed

The Enterprise-ProPublica review of criminal records covered all 334 people freed by the board from 2008 to 2017. We excluded those who have not yet been free for three years from our recidivism calculations, as is the state’s research standard, but we did include them in a tally of the total damage to people and property.

Most of the people released by the board in the last decade were not accused of new crimes. But among those arrested after their release, two-thirds were charged with violent crimes, from minor assault to murder.

Those cases involved 63 defendants freed from 2008 to 2017 and attacks on at least 155 people.

Family members were those most often hurt seriously. The 25 people identified in court records ranged from kids and girlfriends to parents and siblings. They were shoved into walls, punched, choked and chased with knives.

In 2011, the board decided that Josiah Schindler was not affected by a mental disability, despite his mom later telling a judge he was diagnosed at birth and had undergone numerous brain surgeries related to his condition. After he was freed, he was repeatedly charged with nuisance and property charges.

Last year, he beat his mom at their home. An automatic restraining order was placed, as is common in domestic violence cases. To have the order lifted and to return to caring for her son, a judge ordered the mom to group therapy.

This summer, Schindler was sent back to the Oregon State Hospital for treatment until he was mentally fit enough to enter pleas in his ongoing cases.

Others freed by the review board were charged with mostly minor assaults involving at least 32 first responders. Court records show some hit, bit or spit on police officers, medics and jail officers.

In 10 cases, service workers at fast food restaurants, grocery stores and gas stations were attacked or threatened.

One man freed by the review board soon stalked a woman, walking around the block repeatedly to look in the window of the hair salon where she worked. After Cody Adams was convicted and given probation in that case, he stalked another woman. He repeatedly entered her coffee shop and lingered despite being told to leave. Once, he stole a cinnamon twist. That case was dropped because the woman said she wouldn’t prosecute if he promised to leave her alone.

An additional 16 criminal cases involved apparent strangers.

Public records also documented self-harm, attempted suicides and frequent stints of homelessness after people were freed by the state board.

The Oregon State Hospital said nine people released by the board were returned to its care under a civil commitment, which requires a court to find that someone is an immediate risk to harm themselves or others. One person was committed just three months after being freed by the review board.

Courts sent an additional 19 people to the state hospital for mental health treatment so they could understand proceedings in their new criminal cases.

Members of the Psychiatric Security Review Board defended their “exceptional record” and said arrests and civil commitments were not necessarily evidence that a person they had released was dangerous.

“Did the victim feel this was the only way to get the offender mental health treatment and/or resources? Did the county mental health provider attempt to civilly commit the client to avoid a criminal act, but could not meet the ‘imminent danger’ threshold? Were the police attempting to get the offender some help?” board members wrote in a joint statement. “Given that these complexities add context to these findings, we would caution against any interpretations made from these statistics.”

Bort also criticized the Enterprise-ProPublica analysis as too focused on “potential mistakes that are made and who is not doing enough to address those mistakes.”

Dr. Joseph Bloom, who the board has repeatedly turned to for help studying the system, disagreed, saying the analysis was a critical measure of how well the board rehabilitated the criminally insane and if the services those Oregonians received once free were adequate. The retired forensic psychiatrist once served as dean of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University and is a former president of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

Bloom wrote in 1986 that there was at least a “subgroup” for whom “psychiatric treatment had no effectiveness in preventing criminal behavior.” Later research would support this: Although people with mental illness are overrepresented in the criminal justice system, a relatively small percentage of their crimes are directly tied to symptoms of their illness, making health treatment alone ineffective at reducing new crime.

Bloom, now living in Arizona, defended Oregon’s system as more equitable than those in other states, but said the Enterprise-ProPublica findings troubled him.

“The system works, I think, aside from discharge. I don’t know if (that) is working,” he said. “There needs to be some review of what the issues are.”

Free After Months

The board freed Ashmus about five months after he was found not guilty by reason of insanity for a string of assaults and a burglary that could have sent him to prison for 21 years.

Bort defended that decision as routine, a result of the facts and Oregon’s law, even if common sense might suggest otherwise. What Ashmus did next is a grim illustration of what is at stake when the board decides to free someone doctors warned was dangerous.

Ashmus’ violent behavior and struggles with drug use began when he was a teenager. His younger sister was diagnosed with cancer at age 12 and died four years later. The alcohol wasn’t enough to dull the pain, and so he said he began using heroin and meth. After 18 months in prison on a burglary conviction, Ashmus was sober for 17 years. He said he focused on being an attentive father to his young daughter.

But then Ashmus fell in love with a woman who used meth. Within a year, he resumed his use of the drug and began to deal when they broke up. One night, he was beaten and robbed by friends.

“I was lured to a dark place at night,” he wrote in a letter from prison. “Two people I didn’t see came out of the darkness behind me with baseball bats and beat me till I was unconscious. I was to find out months later from a witness, they actually broke one of the bats on my head.”

Ashmus started to have nightmares whenever he slept. He would have angry outbursts and was irrationally irritable, punching the wall when he got frustrated. He was on edge, constantly nervous. He told doctors he had flashbacks to his assault and had “racing thoughts.”

He said he was diagnosed with PTSD by a community mental health program. State records confirm that he received care, including counseling from a social worker, but did not detail his diagnosis.

In 2010, Ashmus went to court on a string of charges. In one case, Ashmus said he downed 15 Valium pills and robbed a friend’s house of a large TV during an apparent drug-induced blackout. He also faced a serious assault charge related to attacks on his ex-girlfriend.

Because of his ongoing mental health treatment, his attorney advised him to have an evaluation and consider the insanity plea, which would send him for care rather than to prison. Going to the state hospital seemed much better than six years in prison, the plea deal he said he was offered by prosecutors.

“I used the insanity plea because it was the fairest thing being offered to me and I clearly needed help,” he wrote.

A local clinical psychologist examined him for the court, diagnosing Ashmus with post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. James Wahl wrote that PTSD, at least, was active at the time of the crimes and so Ashmus “lacked substantial capacity” to understand and follow the law.

As part of a December 2010 plea deal, a judge placed Ashmus into the custody of the Psychiatric Security Review Board for up to 21 years.

Five months later, the board freed Ashmus.

Doctors from the Oregon State Hospital argued that he did not, in fact, have a mental illness. Records note that psychiatrists there diagnosed him with a personality disorder — a behavioral issue, not a disease.

“It is apparent that Mr. Ashmus was voluntarily intoxicated at the time of his crime, which does not excuse criminal behavior,” Dr. James Peykanu wrote.

The board accepted the doctors’ conclusion and freed Ashmus. Because he had been acquitted of his crimes, Ashmus could not be retried or simply moved to prison. The U.S. Bill of Rights bars prosecutors from taking people to trial more than once for the same crime, a concept known as double jeopardy.

Ashmus wrote that he does have PTSD and anxiety disorder with depression. He said he lied to the board and went along with the state doctors’ assessment that he did not have a mental illness because he wanted to be free. In the grand scheme of things, he feels justified.

“It was the right thing to do,” he said. “Dr. Wahl, nor the doctors prior to him, did not make a mistake in my diagnosis. The mistake was clearly I was sent to a facility that had nothing to offer someone with PTSD other than medicating them.”

The board’s decision to free Ashmus came despite warnings he was dangerous.

“Mr. Ashmus is estimated to be at an elevated risk for engaging in aggressive behaviors and his risk to harm others should continue to be monitored,” psychologist Matthew Sturgeon wrote in one progress note for the board.

Sherie Chaney, a mental health nurse practitioner, wrote in a later update that Ashmus “is frequently deceitful as well as impulsive” and often rationalizes “having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from others.”

While he was in custody at the hospital, Ashmus did not respond well to treatment. He refused medications, initially avoided group therapy and was moved into the most secure unit. Although he did not cause anyone physical harm, hospital staff documented repeated threats of violence as well as invitations for female staff to meet him alone in dark places. After one phone call, he punched a wall.

Ashmus’ mother said his time at the state hospital was traumatizing, including because a woman killed herself while he was there. State records also note he was repeatedly assaulted by another patient in his unit. Ashmus needed help, his mother said, but she did not think the secure state hospital was where he belonged.

He said he didn’t have the help he needed once free either. Although officials from the state hospital and the review board insist that a discharge plan is prepared for every person they release, Ashmus said, “they didn’t prepare me in anyway.”

Under its current practices, the board does not examine in detail the plans for a client’s treatment after release, leaving those specifics to county mental health officials. That’s a contrast to the board’s oversight of defendants moving from the state hospital to community treatment, which requires a five-step review and is sometimes delayed until the board is satisfied that public safety is adequately protected.

Seven months after he was freed by the board, Ashmus was high on meth as he watched his 8-year-old daughter and the 3-year-old grandson of his girlfriend. He wrapped his hands around his daughter’s neck, throttling her. He then picked up the boy, threw him in the air and tossed him across the room. In Coos County court, he pled guilty to criminal mistreatment in the first degree and was given three years of probation. Neither child was seriously injured.

In February 2012, just two months later, he was charged with burglarizing a home in North Bend, but the case was dismissed when the victim did not appear before the grand jury.

A year later, he was arrested for stealing gasoline from an electrician’s truck. Although he had a gun, which is illegal for felons, he was not charged for that crime. He spent four days in jail.

About a year after that, in August 2014, police charged him with raping and strangling a 28-year-old woman.

According to court records, Ashmus, then 42, flashed his genitals at the woman. After she said she “did not want to have that kind of relationship,” he raped her. He was sentenced to 19 years in prison. Today, he still insists he is innocent.

Unavoidable

Board members said they do not have an opinion about whether Oregon law gives them enough discretion to make decisions that protect public safety. They also declined to “take a position” on other elements that make Oregon’s law and their interpretation of civil rights different from most states.

Bort, who became director this summer, said the agency wants to improve, of course, but described cases like Ashmus’ as unusual but unavoidable.

“Every once in a while, there might be somebody who, despite all the intensive treatment they received, does not internalize it,” she said.

Bort said the board should not be held responsible for what insanity defendants do after they’re freed — even if the results are devastating. Doing so, board members said, was like holding responsible judges, prisons and probation officers for releasing people who go on to commit new crimes.

Bort defended the board’s actions in the Ashmus case as an example of its careful, prudent process for making decisions.

“In that case, the hospital had the gift of time to see what he looked like without any medications, what was left when everything cleared up,” she said.

“And then, as your research showed, he went out and was dangerous again.”

Read more:

Jayme Fraser is a reporter for the Malheur Enterprise, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network. She’s spending the year examining the way states manage people with mental illnesses who commit violent crimes — in Oregon and nationally. Email her at [email protected] and follow her on Twitter @JaymeKFraser.