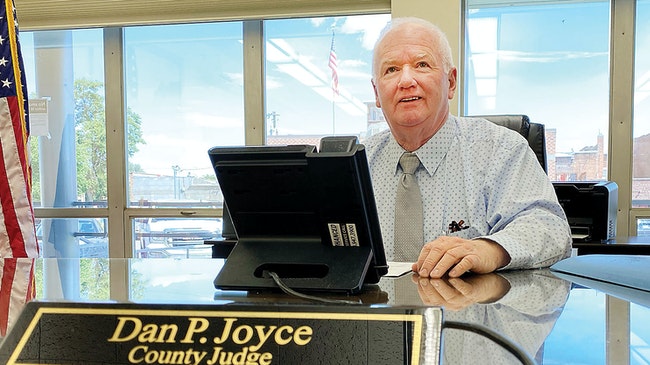

Malheur County Judge Dan Joyce, asked about the performance of Gregory Smith & Company in running the county economic development effort, said he hasn’t had any complaints. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

Greg Smith couldn’t remember much about the audit he said was conducted of the county department he runs.

Audits are typically independent evaluations, done to examine finances or to assess performance.

He said in an interview last fall that it was “correct” that the Malheur County Economic Development Department he leads had been audited.

Smith couldn’t remember, though, when the audit was done.

“I’d have to go look at my calendar.”

He didn’t think the audit resulted in a written report, which would be standard.

“I believe it was an interview,” he said, “by the county.”

He couldn’t remember who interviewed him.

“I’d have to go look at my calendar to see to remember,” he said.

But there was nothing to find.

There was no interview, no calendar entry. The account of an audit was fiction.

Smith’s suggestion that his agency had undergone an outside inspection represents the challenge of pinning down the truth about what he is delivering for taxpayers of Malheur County.

An Enterprise investigation over six months provides the first independent accounting of the agency’s performance. The report is based on several thousand pages of public records and interviews with government officials and economic development authorities.

They show an agency without oversight, producing uncertain results, managed by remote control from Heppner.

Gregory Smith & Company has been paid more than $900,000 since 2013 to run the county agency.

Yet, unlike other economic development agencies, Smith produces no annual report chronicling what the county economic development department accomplished.

The Small Business Development Center at Treasure Valley Community College tracks the number of jobs its team saved or created, how many businesses it helped start and how much money was invested in local business.

Snake River Economic Development Association likewise tracks in detail its performance each year, including the number of site tours it conducted for potential new employers.

Smith’s operation produces none of that.

Such economic develop work is especially vital for Malheur County, whose people endure the highest poverty rate and among the lowest incomes in Oregon. While the West has been booming, the population in Malheur County has stayed essentially flat for a decade.

Economic development is supposed to change that.

Smith gave one interview to the Enterprise on the matter last fall, but not voluntarily. He was ordered to do so by Malheur County Judge Dan Joyce. He was combative and insulting, cutting off the interview after 30 minutes.

He didn’t respond to subsequent written questions or address excerpts from this story sent to him ahead of publication to review for accuracy.

Greg Smith of Heppner, who runs the Malheur County Economic Development Department, cut off an interview at 30 minutes after being questioned about his agency’s performance. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

Greg Smith of Heppner, who runs the Malheur County Economic Development Department, cut off an interview at 30 minutes after being questioned about his agency’s performance. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

HOW HE WORKS

Smith and his company do this work for the Malheur County Court, the county commissioners. They retained his company in 2013 and every year since, the commissioners renewed the deal. The company is paid $9,000 a month, and from that it is expected to pay staff, run an office, and cover most of the expenses of running a county economic development agency. The contract says Smith’s company is to “expand the tax base and create quality and family wage jobs for citizens of Malheur County.”

The legal document includes 12 paragraphs listing “deliverables” – tasks – the company “shall” perform each year.

County officials said the tasks have been unchanged year after year, and county officials don’t independently assess whether they get done.

One required task is a “work plan,” for instance. A work plan typically lays out an organization’s goals and objectives and how they will be achieved.

Joyce said he’d have to “think about that a little” as to whether he has ever seen such a plan in the past eight years.

There was one, Smith insisted in an interview.

Two months earlier, the Enterprise in writing sought from Smith “any public record documenting completion or performance” of such a work plan. Smith said he in a later interview that he hadn’t released the plan because the Enterprise “didn’t ask” for it.

District Attorney Dave Goldthorpe, invoking the public records law, subsequently ordered Smith to turn over the document.

But there wasn’t one.

Rather, Smith said, “Our website represents our work plan.”

Smith is also required to “update Malheur County economic profile documents.”

When the Enterprise requested any record dating back to January 2020 showing his agency’s work on such documents, he responded: “Malheur County Economic Development is not in possession of requested records.”

The contract requires that Smith “develop an available lands inventory for all of Malheur County.”

Responding to a public records request, Smith provided a printout of 11 properties in Malheur County. The list was from a state-run website called Oregon Prospector. Only one property had been entered by Smith’s team – a proposed county industrial park in Nyssa that the county doesn’t have the money to develop.

His company also is paid each year to produce “a distinctive, competitive and effective marketing strategy to recruit new businesses to Malheur County.”

Smith insisted in the interview that there was a marketing plan done in 2020-21 but he hadn’t disclosed it, falsely claiming the Enterprise hadn’t requested it.

Under orders from the district attorney, Smith weeks later released a one-page document “Malheur County Economic Development Marketing Plan.” It listed seven “strategies” – from “appropriate signage at the industrial park” to “create and update digital marketing packets.”

Records released by Smith didn’t include any “digital marketing packet” and the economic development agency didn’t respond when recently asked for one.

Data embedded in the document that Smith turned over showed that it was created on Dec. 7, 2021 – one day before it was released to the Enterprise and nearly six months after the contract period was up. Smith said he had not a single other document referencing that plan and no documented marketing plan in the previous two years.

The county commissioners charged with overseeing Smith’s performance seemed unaware of the details of what they were paying Smith’s company to do.

In separate interviews, Malheur County Judge Dan Joyce and Commissioners Don Hodge and Ron Jacobs couldn’t answer questions about the required tasks.

Joyce said he assesses Smith’s performance with one measure.

“I have never had a complaint about Greg – not one,” said Joyce.

Commission Don Hodge said county officials and the public need accountability from the economic development operation. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

Commission Don Hodge said county officials and the public need accountability from the economic development operation. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

Hodge said Smith was “to be working on these services” required under the contract and that “we discuss it quite a bit” when the contract comes up for renewal.

In fact, nothing was said about those required services last June when the commissioners re-upped Smith’s company for another $108,000.

Hodge couldn’t identify the most significant accomplishment by the county agency in that prior year.

“I don’t have anything in hand to tell you,” he said.

And Jacobs, who joined the commission in January 2021, said he hadn’t asked what Smith had accomplished before voting last June to renew the contract.

The commissioners expressed similar expectations for their economic development department – lure employers and create jobs to bolster the local economy.

The commissioners cited the same examples to demonstrate that Smith had done just that.

They relied on talking points prepared by Smith himself to help commissioners address questions about his performance.

Joyce, Hodge and Jacobs each cited Somewhere Out West Coffee as an example of a new business, but couldn’t say how many jobs had been created.

Ashley Buckingham, a rancher who lives with her family in Nevada, opened her coffee stand in a former service station building on U.S. 95 in the Oregon border community of McDermitt -– nearly 200 miles from Ontario.

“Greg and his team were extremely helpful,” Buckingham was quoted as saying in a press release put out in October 2020 by Smith’s team. “They offered business advice and helped me find resources for startup expenses.”

Whether she employs any Malheur County residents couldn’t be established. Buckingham didn’t respond to telephone and email messages seeking an interview or respond to written questions about her experiences with Smith.

Another business that Smith prepped commissioners to tout was Big Loop Pizza and Subs in Jordan Valley, which opened in March 2021.

“Malheur County Economic Development provided invaluable service as I pursued my dream,” owner Shelley Gluch said in the press release.

The number of workers at the new business couldn’t be established. Gluch didn’t respond to telephone and email messages seeking an interview or respond to written questions about her experiences with Smith.

Other business owners haven’t found the help they needed at Smith’s agency.

Tim Martin of Adrian, whose family has grown wine grapes for 20 years, sought help in planning to establish a winery. He already grows grapes as Emerald Slope Vineyards.

He said he had a “very positive” experience with the county economic development department but the agency left him on his own to pursue help with state agencies.

“They’re focused on other things – onions, potatoes,” Martin said.

In the interview, Smith said the No. 1 challenge for Malheur County’s economy is developing a work force.

The county’s unemployment rate is below the state average and area businesses report continuing trouble finding workers.

Smith’s team had one idea to help.

County records obtained by the Enterprise show that Ryan Bailey, the sole staffer based in Ontario at the economic development agency, envisioned doing video interviews with employers who had jobs to fill. Bailey didn’t respond to an interview request or written questions, but the documents show the plan was to film employers one at a time describing job openings and the work available.

The Malheur County office wanted to help Idaho companies recruit as well -– but wanted to disguise its role doing so.

“I wouldn’t want to upset any Malheur County businesses or residents by taking any Idaho businesses,” Bailey said in an email in May 2021. “For interviewing an Idaho business, it will be best if I’m not the face on the video.”

The effort resulted in a single video for a Youtube channel called “Malheur County Area Employers.” The video concerning jobs at Kraft Heinz in Ontario, posted in July 2021, has been reviewed about 20 times. There are no other entries on that channel.

Smith said the county department’s top accomplishment in the 2020-2021 contract year was “providing confidential one-on-one assistance to companies in need.”

Email logs from the agency obtained through a public records request showed the agency received 859 emails in a two-month period last fall. Based on a review of the subject line, only six emails appeared to be inquiries from businesses seeking information or help. Smith was provided the analysis, which he didn’t dispute.

Smith did later produce calendar entries showing his agency working with local businesses. That included time spent helping an Ontario businessman with unpaid state taxes and a contractor who had violated state environmental rules while on a building project in Malheur County.

Here’s a look at how other agencies track their work for their clients. The Small Business Development agency in Ontario issued this graphic snapshot of its work. The office is separate from Malheur County’s economic development agency, which doesn’t produce such reports.

Here’s a look at how other agencies track their work for their clients. The Small Business Development agency in Ontario issued this graphic snapshot of its work. The office is separate from Malheur County’s economic development agency, which doesn’t produce such reports.

‘TEAM EFFORT’

The Malheur County Economic Development Department isn’t alone in trying to build the local economy.

The Small Business Development Center at Treasure Valley Community College focuses on advising business owners and would-be entrepreneurs.

The Snake River Economic Development Association, based in Ontario, takes a regional approach to economic work. The association conducts site tours for would-be employers, helps companies expand, and markets the assets of Malheur County that are useful to employers.

The city of Ontario also funds a community development office, led by Dan Cummings, who works regularly with businesses seeking to locate or expand in Ontario.

Seth Sperry, an economic development officer with the city of Albany, is president of the Oregon Economic Development Association, the state’s leading association of those engaged in economic work.

“Economic development is a team sport,” Sperry said. “If people are taking a whole lot of credit for something, that’s likely not accurate.”

He said blending skills and assets among organizations provides the most impact.

Representatives of other economic organizations in Malheur County agree.

“It is very important to keep our existing businesses strong and healthy,” said Kristen Nieskens, executive director of Snake River Economic Development. “We try very hard not to duplicate services that others provide.”

“If we don’t all share together, we waste our precious resource and time,” said Andrea Testi has run the local Small Business Development Center in Ontario for 22 years.

But how much Smith and his team collaborate isn’t clear, and even the mission of Malheur County Economic Development isn’t evident to some.

“I don’t really know” what is the county operation’s primary focus, Testi said. “I honestly don’t know of the resources that economic development has that they share with our clients.”

Nieskens said Snake River refers clients to the county, but she couldn’t recall the county sending any businesses to her operation for help. She said the county agency doesn’t attend her group’s regular meetings and she was “not aware” that the county agency has a marketing plan.

Hodge, the county commissioner, said he regularly attends weekly meetings of the Ontario Area Chamber of Commerce and Smith “wasn’t at any of them I was at.”

He added, “His name wasn’t mentioned.”

That may be in part because Smith has other obligations besides his duty to Malheur County.

He is the executive director of the Small Business Development Center in La Grande, a contract worth $118,800 a year to his company. He manages loan work for Morrow Development Corp. of Heppner, which pays his company $100,000 a year, and his company provides service to a public utility in Hermiston that won’t discuss its dealings with Smith.

The Columbia Development Authority in Boardman also employs Smith as its executive director under a salary of $144,812. He also draws a $32,000 salary as a state representative.

Commissioner Ron Jacobs said the county probably needs to keep closer track of its economic development agency. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

Commissioner Ron Jacobs said the county probably needs to keep closer track of its economic development agency. (The Enterprise/FILE PHOTO)

LITTLE REPORTING

In contrast to Malheur County’s agency, other economic development services each year prepare detailed plans followed by data-rich reports on what was accomplished.

“We have an annual work plan that is our road map for activities,” Nieskens said. “This helps the staff and the board stay on track with a focus.”

The staff produces an annual Report Card, tracking numbers for leads on new businesses, business retention work, new business start-ups it helped and more. The data is shared going back several years.

Testi said the Small Business Development Center has “multiple strategic plans” to guide its work through the year. Her team produces a detailed report each year on what it got done.

The most recent, for 2020, tabulated consulting for 376 clients, the retention of 268 jobs and the creation of another 13, the formation of five new businesses and more than $2 million invested in local businesses. Testi said businesses that rely on the Small Business Development Center are regularly asked to privately share data about jobs, profits or losses and other measures of economic activity.

There is no such information at the county’s economic development agency, based on Smith’s response to public records requests.

In September, the Enterprise requested public records from the county economic development department for a one-year period “to determine the record of performance by Gregory Smith & Company under its contract with Malheur County.”

In response, six weeks and $450 later, Smith produced 16 documents.

Questioned about the handful of documents, Smith responded in an email, “You are not a journalist, but rather a vindictive narcissist who is infatuated with me,” Smith wrote to Editor Les Zaitz.

Some of the records didn’t document work done from June 2020 to July 2021 – the scope of the request. Smith, for instance, provided among the 16 documents a photo of an “open” sign outside the agency’s office -– taken just hours before the batch was turned over to the Enterprise. He also provided a marketing flier from 2018, outdated because it was missing essential information on a business tax.

During separate interviews, the Malheur County commissioners were shown the documents. They were told that Smith represented them as establishing that he had met his contract requirements.

Joyce wasn’t sure what the documents proved.

“There should be some explanation to go with it,” he said.

Hodge said the information “doesn’t answer the question of what he’s done in the past year.”

Jacobs looked over the 16 documents.

“I’m not very impressed,” he said. “We probably need to be keeping a little closer track of them.”

Hodge said the commissioners need to tighten their oversight of the county agency.

“There needs to be accountability for economic development and we as county commissioners need to know and the public needs to know, we need to know what’s going on,” Hodge said.

Contact Editor Les Zaitz by email: [email protected].

PLEASE SUBSCRIBE – The Enterprise is available for $5 a month. Subscribe to the digital service of the Enterprise and get the very best in local journalism. We report with care, attention to accuracy, and an unwavering devotion to fairness. Get the kind of news you’ve been looking for – day in and day out from the Enterprise.