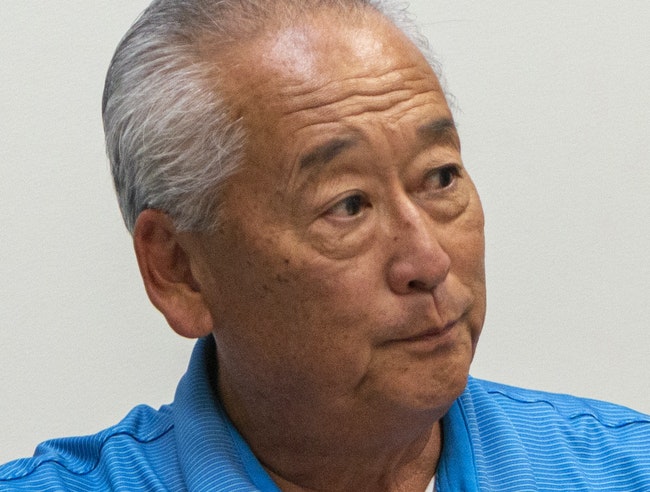

Grant Kitamura of Baker and Murakami Produce Co. of Ontario and president of the Malheur County Development Corp., which is developing a publicly-funded rail shipping center in Nyssa. (AUSTIN JOHNSON/The Enterprise)

NYSSA – Two key players in the effort to construct a rail center in Nyssa appear poised to benefit from the public money invested in the facility.

Yet the two onion industry executives, Grant Kitamura and Kay Riley, say there is no conflict between their public duty and private business. They say they can ably decide how to use millions in public money while negotiating deals that benefit their companies.

Riley is the general manager of onion packing company Snake River Produce in Nyssa, while Kitamura is general manager and part owner of the onion packing firm Baker & Murakami Produce Co. in Ontario.

They are officers of the Malheur County Development Corp., the public company created by the Malheur County Court to oversee the creation of the rail center.

And they are founders and officials of Treasure Valley Onion Shippers, a business set up to privately negotiate for preferable shipping terms for using the Nyssa center. The company is dealing with the expected rail center operator, Americold. The idea for the shipping consortium was Americold’s, said Riley.

“Americold wanted to deal with one entity rather than all the individual shippers,” said Riley.

The tangle of private and public interests and ambitions raises questions about conflict of interest between the roles of Riley and Kitamura in the Treasure Valley Onion Shippers, the public company and as executives of private onion firms.

Riley and Kitamura said in separate interviews last month that their goal is to help the local economy.

“I am doing this for the industry. It is not like I will cut a fat hog off this deal. It isn’t going to pad my pocket. If I am being accused of being self-serving, I don’t think that is correct,” said Kitamura.

The two were picked for seats on the development company board without having to apply in a process that wasn’t open to the public. They were selected by local elected leaders who chose them for their experience in the onion industry, according to interviews.

Once on the board in 2017, they became public officials, governed by state ethics laws.

Riley said he did not receive training on state ethics laws. Kitamura said he did receive training on ethics laws when he was a member of the Oregon Board of Agriculture, but not when he became a director of the development corporation.

The absence of training or orientation in ethics law, while legal, can leave appointed officials without a clear sense of how their conduct could be viewed by taxpayers.

BIG PROJECT, BIG AMBITIONS

The Treasure Valley Reload Center was billed to help local onion shippers and other agricultural interests ship their product to the Midwest and to the East Coast faster and cheaper than truck transport.

In 2017, then-state Rep. Cliff Bentz engineered legislation to deliver $26 million in public money to Malheur County in a deal meant to show support for eastern Oregon’s economic future.

Since then, the rail project being managed by the Malheur County Development Corp. board has repeatedly missed key project deadlines, subsisted on additional money from county coffers, and has functioned in recent months without regular budget reports as costs have climbed.

The two men at the apex of the project have been in the onion business for decades – and often in leadership roles.

Riley has worked with onions for over 30 years and became manager of Snake River Produce in 1999. He and partners bought the onion packing operation in Nyssa from his grandfather’s company, Muir-Roberts Co. He was president of the National Onion Association from 2008 to 2010.

According to the Snake River Produce website, Riley was Nyssa Agriculturist of the Year in 2018, chaired the Idaho/Eastern Oregon Onion Committee, and was president of Certified Onions Inc. He also has been a leader in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Kitamura grew up in Ontario and joined Murakami Produce in 1980. In 2017, it merged with Baker Packing. He has been president of the Idaho/Oregon Fruit and Vegetable Association, served on the board of the National Onion Association Board and was a member of the executive committee of the Idaho/Oregon Marketing Order.

He has served on the board of Treasure Valley Community College Foundation and the Ontario hospital when it was known as Holy Rosary Medical Center. County records show he and his businesses own more than 40 properties in Malheur County.

In 2018, Gov. Kate Brown appointed Kitamura to the Oregon Board of Agriculture but he stepped down in 2020 with plans to move to Idaho.

In later legislative testimony about Oregon’s estate taxes, Kitamura said he made the move because Oregon inheritance exemptions “are much too low for many Oregonians.”

In their role on the board of Malheur County Development Corp., Riley and Kitamura were involved in crafting the lease with Americold to operate the reload center. Both voted on the terms of a final agreement that real estate experts said was unusually generous to Americold.

The county’s economic development director, Greg Smith, made clear that the better deal the public could give Americold, the better deal Americold could give onion shippers.

Kitamura and Riley were involved in the private negotiations with Americold as members of the onion shippers’ consortium.

“I am president of Treasure Valley Onion Shippers. The board of Treasure Valley Onion Shippers and Americold discussed our agreement, which is confidential,” Riley said.

Kitamura also said in an interview that the individual members of the onion firm negotiated with Americold.

The lease of the public project, still not signed by Americold in spite of a June 15 deadline, provides for rent at a fraction of what is standard and a no-fault clause where Americold can abandon the project if finances don’t pencil out. The lease provides that if the company operates in Nyssa for 20 years, it can get the multimillion-dollar project for $1.

Kitamura said that provision is a “good carrot for them to perform.”

“If they’re not competitive we will not use the facility,” said Kitamura.

Kitamura said in June that the state money was essentially paying for reduced shipping rates for local onion producers.

“It is for a facility that will reduce our shipping rates. It isn’t a direct subsidy,” said Kitamura.

Shippers now use a mix of trucks and train cars. An early estimate by project developers was those costs would be cut by about $2 million a year.

As negotiations with Americold continued over the summer, the state agency overseeing the project asked for an affidavit declaring that the companies making up the Treasure Valley Onion Shippers were committed to using the rail facility. The state Transportation Department has said that commitment is key to the financial feasibility of the Nyssa center.

The state agency got something considerably less binding. Kitamura and Riley each signed letters saying their companies had a deal “in principle” with Americold. No other shippers issued such a letter.

Kitamura said state officials agreed that letters from him and Riley would suffice to meet a June 15 deadline. Even that date was months later than state and county officials expected.

“It was too short order to get all of the members to sign,” said Kitamura.

Riley echoed Kitamura.

“It was because of time restraints. They (Americold) needed to have something to show to the state to move forward and there was no time to make that agreement with everybody,” said Riley.

Kitamura and Riley emphasized there still is no final deal between the onion shippers and Americold.

The summer sequence of negotiations was a mixture of private and public efforts and Kitamura said he represented the onion industry, his company and the public.

“Probably primarily the onion industry,” said Kitamura. “As a (development corporation) board member, I wear two hats. I am also a member of TVOS. As a member of TVOS I have access to information that isn’t public.”

Riley also said he wore “two hats” in talks with Americold.

“I certainly wasn’t wearing an MCDC (development corporation) hat when I was negotiating with Americold. I was wearing a Treasure Valley Onion Shippers hat, so in that regard I probably wore those two hats,” said Riley.

ARRAY OF RESPONSIBILITIES

The responsibility for overseeing the rail project is somewhat murky.

Malheur County Judge Dan Joyce said that “with respect to this project, the oversight comes from the Department of Transportation.”

Erik Havig, manager of the state Transportation Department planning section, said his agency “has general oversight of the project in the sense that ODOT is the awarding agency responsible for overseeing taxpayer funds.”

He said in an email that the agreement puts the prime duty on the development company, which is receiving the state money.

“The agreement really puts the responsibility for complying with the terms of the agreement on the recipient – things such as conflict of interest, reimbursing only eligible costs, obtaining the necessary permits and designing and constructing the facility to state and local standards and codes among others,” said Havig.

Havig said, though, the state “does not track every aspect of these requirements.”

Joyce said he looks to the development company to adequately manage the project.

“I expected them to take over the project and do it all, period. I expected them to do whatever necessary to get it up and running,” he said.

Joyce said the development company was designed by the county to act independently.

“When you put together an organization like that, that is what your hopes are,” he said.

Joyce said he sees no conflicts for Kitamura or Riley in representing both the public and their businesses.

Early in the rail center planning, officials discussed creating a board of local business people to act as a barrier to potential conflicts of interest.

That board never took form.

“We ended up inviting several businesses to join us, one of whom accepted the invitation and participated in a single meeting. The other businesses elected not to participate,” said Smith, economic development director and the project manager of the rail project.

And despite the complexity and cost of the project, the development board has frequently gone weeks without meeting. What meetings it does hold usually last no more than 30 minutes.

A LOOSE ETHICS LAW

Oregon’s state ethics system was given an F grade by the Center for Public Integrity and Public Radio International in a 2015 report. Oregon was also ranked 42nd among 50 states in 2015 in the report.

“Lines are easily blurred in Oregon government, and ethical lapses and partisan abuses of power – while often not criminal – have been smoothed over by both political maneuvering and etiquette,” according to the center’s report.

“The truth is there may not be a statutory conflict of interest, but what is statutory is oftentimes different than an appearance creates,” said Patrick Hearn, former executive director of the Oregon Government Ethics Commission. “Something can look like it is very unsavory but yet it complies with the law.”

According to Ron Bersin, the current ethics commission executive director, a conflict of interest occurs when a public official makes a decision on public business that can deliver financial benefit to themselves or someone in their household.

Riley said that conflicts of interest were “discussed in board meetings.”

“What we were supposed to do is to represent the best interest of the county and the state,” he said.

State law provides different standards for dealing with potential versus actual conflicts of interest, and for appointed versus elected officials.

For appointed officials like Riley and Kitamura, any potential conflicts of interest have to be disclosed to the officials who appointed them to the development corporation. In their case, that would be Joyce and the two county commissioners. Those officials would then have been tasked with handling the matters in which the onion executives had conflicts, but they would have the option of letting the onion executives go ahead and make key decisions anyway.

However, both Kitamura and Riley said that they didn’t have conflicts of interest in the first place.

“I had the full support and approval of my board,” said Riley, referring to Snake River Produce.

Bill Gary, the state’s former deputy attorney general, said that Oregon lawmakers deliberately chose to not prohibit public officials with a conflict of interest from voting on related matters because of the challenges of governing in small communities.

In such places, he pointed out, conflicts of interest may arise more often due to how interrelated families and businesses can be.

“You would run the risk of making it impossible to get anything done,” he said.

The law requires elected public officials to declare any conflicts before voting, and elected officials can face consequences with voters if they don’t act appropriately in regard to their conflicts of interest.

For appointed officials, however, the mechanisms of accountability are less obvious.

“If you think the public official is not complying with ORS 244 (the ethics statutes), then you file a complaint with the Oregon ethics commission and they decide whether a violation has occurred and whether to impose a penalty,” said Dan Meek, a Portland-area lawyer and advocate for stronger ethics laws.

But Gary said the ethics commission was “understaffed.”

“A fair criticism of the ethics laws in Oregon would be that they could be enforced more aggressively and more fairly than historically they have been,” said Gary.

Meek said Oregon’s ethics laws are weak.

“Oregon has really shamefully shambolic ethics laws and almost anything goes,” he said. “Oregon’s conflict of interest law is just absurdly weak.”

PUBLIC, PRIVATE INTERESTS

Kitamura said that while he didn’t personally invest in Treasure Valley Onion Shippers, Baker & Murakami Produce Co. did.

Riley said his company also is part of Treasure Valley Onion Shippers but said there is no “ownership” but “there is a membership.”

Kitamura said one goal of his multi-tiered role with the rail center was to help the local economy.

“I think my duty was to the industry and the community to help develop a viable method to compete with trucks to get lower freight rates and a better return for growers, which, in turn growers would be able to continue forward and keep the industry viable,” said Kitamura.

However, there is no evidence the local onion industry would diminish without the rail center. And roughly half the onions to be shipped would come from Idaho operations, project organizers have said.

Kitamura said the shipping facility would trigger a “ripple effect” through the local economy. “My role, primarily and initially, was to help put this facility together and find a handler, someone to run the business,” said Kitamura.

“It will bring revenue into the county, keep the industry viable and continue to be the second leading agriculture commodity in the county,” said Kitamura.

Riley agreed.

“We feel like the onion business is an asset to the local community. We provide jobs and pay taxes and do all of those things, and we are at a great disadvantage here, and the state recognized that and granted this money to help us be more viable. If we are more viable, the county benefits,” said Riley.

Kitamura said the rail center will save money for firms such as Baker & Murakami.

“The freight rate is always lower than trucks,” said Kitamura.

As ambitious as the rail center plan is, it won’t add a large number of jobs to the local economy nor change the local onion industry in a significant way.

No more onions than usual will be shipped from the center, industry officials have said.

ONIONS AND JOBS

The most recent data provided by the development company showed 490,000 tons of onions are shipped out of the region each year. Project organizers forecast that about one-third would go by rail.

When asked in June what percentage increase in onion production would occur because of the rail center, Smith said he didn’t know.

“Boy, I couldn’t give you an answer on that,” said Smith.

Riley said the Transportation Department hopes there will be a boost to the local onion industry with the rail center.

“The real key to this is being able to move the crop we currently have. Whether that evolves into more production in the future, that remains to be seen,” said Riley.

Smith also couldn’t define when asked in a public meeting in June how many new jobs will be created when the rail center is built. He has worked on the project for more than three years.

“It is a fair question. I’d have to sit down and visit with Americold and the shippers to give an accurate answer,” said Smith. He has yet to produce a new projection.

A 2018 market feasibility study projected construction of the facility will produce 148 jobs while it was being built but 16 full-time slots once operating.

That’s in contrast to the 125 jobs touted by officials when the project was first proposed.

News tip? Contact Pat Caldwell at [email protected] or Liliana Frankel at [email protected].

Previous coverage:

Reload center construction costs climb past project budget

WATCHDOG: Malheur County’s bid to grab $15 million in federal money stymied by errors in application

EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM – Available for $5 a month. Subscribe to the digital service of the Enterprise and get the very best in local journalism. We report with care, attention to accuracy, and an unwavering devotion to fairness. Get the kind of news you’ve been looking for – day in and day out from the Enterprise.