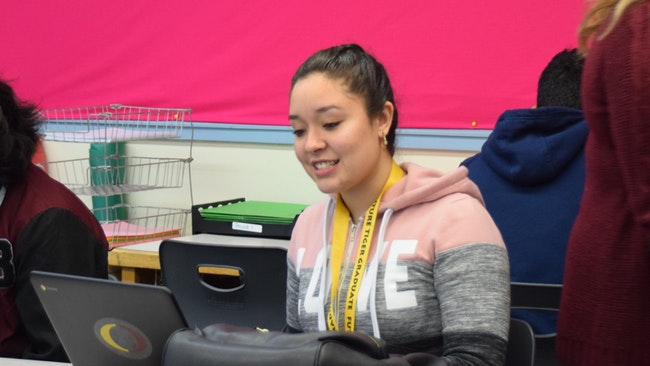

Sophomore Mariana Bobadilla works on her studies at Ontario High School. A U.S. citizen, she moved with her family to Mexico at age 4 but returned to the U.S. last August to finish high school. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

Sophomore Mariana Bobadilla works on her studies at Ontario High School. A U.S. citizen, she moved with her family to Mexico at age 4 but returned to the U.S. last August to finish high school. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

Andrea Perez was born in Ontario. She was 7 and had just entered second grade at Cairo Elementary School when her parents moved the family to Mexico.

She returned to the U.S. unaccompanied at 16 to finish her education in the first place she called home. Now 19, Perez dreams of earning her doctorate and becoming a medical researcher.

Educators believe there are many more students like her.

“We think it’s a national trend,” said Anabel Ortiz-Chavolla, director of the Migrant Education Program at Ontario High School. “These students are American citizens. They’re coming back because they want to get their education.”

The Oregon Department of Education doesn’t track the number of American students like Perez.

But more than half a million U.S.-born minors live in Mexico, according to a study published last year using Mexican census data.

That number, which stood at about a quarter million in 2000, exploded over a period of 10 years, pushed up by the U.S. recession, according to the report.

In Mayra Rodriguez’s class at Ontario High School, 12 students share Perez’s experience. They come to Rodriguez, who teaches English language development, to help retrain their tongues to speak English that they learned as young kids, and then forgot as they grew up in Spanish-speaking countries.

Their stories are all different. Some had parents who were deported and took their American-born kids with them. Others, like Perez’s parents, uprooted everything to care for a terminally ill family member. They did so knowing that their undocumented status would make it a one-way trip.

“There are a lot of students here without their parents,” said Rodriguez.

[ KEEP YOUR LOCAL NEWS STRONG – SUBSCRIBE ]

Mayra Rodriguez gestures to a student as she teaches English language development at Ontario High School. She works with several students who are U.S. citizens, but are learning English after spending much of their early childhood in Mexico. Several have returned to the U.S. unaccompanied to finish school here. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

Mayra Rodriguez gestures to a student as she teaches English language development at Ontario High School. She works with several students who are U.S. citizens, but are learning English after spending much of their early childhood in Mexico. Several have returned to the U.S. unaccompanied to finish school here. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

Some come unaccompanied, leaving their parents behind to stay with aunts, uncles and cousins in the U.S. A common goal is to finish high school and go to college.

Almost all left the U.S. as young kids. They grew up speaking Spanish. Some left before they started school.

Like Mariana Bobadilla. Now a 10th grader, she was moved to Mexico at age 4. For a while, she lived in Tijuana and crossed the border every day to go to school. Bobadilla finally came to the U.S. permanently last August.

She’s a good student, she said quietly as she sat in Rodriguez’s class, but she struggles with English the most.

“I like to participate in class,” she said, but the language barrier makes it difficult.

She wants to go to school to become a surgeon. She said she knows the opportunities are better here.

Another student, now 17, was born in Ontario but moved to Mexico at age 6. He remembers when he first enrolled in school in Mexico. Teachers scolded him for answering questions in English. With no one around to practice, he began to lose the language.

Now he lives with an uncle in Ontario. His parents and siblings stayed behind in Mexico. His goals are to perfect his English and go to college.

Then there’s Everardo Diaz, who was born in Oregon, but was raised by his grandparents in Mexico for 14 years. Now a junior in Rodriguez’s class, Diaz recalls that when he first moved to Mexico, he would cry in school because he didn’t understand Spanish. Now, he said, it’s the other way around.

Diaz likes languages. In Mexico he took it upon himself to learn Huichol, an indigenous language from the state of Jalisco.

“But for some reason English doesn’t stick,” he said, speaking in Spanish.

He dreams of going to college, maybe culinary school, and returning to his grandparents’ home. He’s started saving up to build a house near them.

In Malheur County, Diaz worked in the onion fields, but recently quit to focus on school. Working in the fields was easier, he said, because he didn’t have to speak English with anyone.

Rodriguez said many of her students have part-time jobs, mostly in the fields or at Dickinson Frozen Foods in Fruitland.

Perez gave farmwork a shot, too. It would be easy, she thought. After all, her parents had been farmworkers when they lived in Oregon.

She lasted one day, she recalled with a laugh. She moved on to Dickinson, where in a matter of weeks she was promoted. She worked there for five months before work started to interfere with school.

“A lot of them gravitate toward that work because they have family there and the application process for other jobs and having to interview in English is frightening,” Rodriguez said.

Even though these students are American citizens, she thinks some still have a fear of deportation because their parents remain undocumented.

“They feel like they can’t do anything to mess up this opportunity,” Rodriguez said.

She can tell when they were top students in Mexico.

When Rodriguez asks the class what questions they want to know how to ask in English, Bobadilla raises her hand and asks her in Spanish: how do you say “How can I raise my grade in your class?”

Rodriguez turns toward another student, whom they jokingly call Mr. America because his level of English is more advanced. He pauses, then throws out the first two words correctly.

Andrea Perez moved back to Ontario, where she was born, two years ago to finish high school and achieve her dream of earning a Ph.D. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

Andrea Perez moved back to Ontario, where she was born, two years ago to finish high school and achieve her dream of earning a Ph.D. (The Enterprise/Yadira Lopez)

For Perez, who used to borrow biology books from Rodriguez’s class, a 78% on an essay is a “low grade.”

The ambitious 18-year-old gained fluency in English in one year. She’s now in honors English and proudly shares her 92% grade in the class. Letting it slip is not an option.

She was recently admitted to Oregon State University’s honors college.

“My drive to have a successful career brought me here,” she said. She left her mom and dad and three younger siblings in a tiny town in Puebla.

Her father, a bus driver in Mexico, couldn’t afford to send her to the coveted and expensive university she favored. She was disillusioned with the corruption and violence she witnessed.

“For some students it wasn’t safe,” Rodriguez said.

One student was urged by her mother to go back to the U.S. to flee an abusive father. Others were living in neighborhoods where their lives were at risk.

In her classroom, Rodriguez focuses on creating a home for her students.

A few weeks before the holiday break in December, she went over Christmas vocabulary with them. Stockings, Christmas tree, chimney. What goes inside the stockings, she asked. Coal, candies, cookies, they responded.

The assignment that day had them record themselves in English. Bobadilla and Diaz whispered self consciously into their recording devices.

Some of her students who recently migrated back to the U.S. share that they are sad or stressed. A lot of them feel the pressure to be successful; but sometimes they drop out, urged by family members to take up jobs instead of college.

“They’re coming back at that age when they most need their parents,” said Rodriguez.

The transition comes with challenges.

What do they miss about Mexico?

“Todo,” Diaz and Bobadilla say in unison – “Everything.”

When Perez first moved to Mexico, she spent the first year pining for home in Ontario, for her second-grade teacher at Cairo, for the Burger King where her parents would take the family on Sundays.

Students like her carry a double identity. One student in Rodriguez’s class shared that in Mexico they called them “pochos” – slang for American. But here, they are “nopaleros” or Mexican.

Despite the language barrier, Rodriguez said the students catch on quickly. They usually have an instructional assistant or a peer that can help translate in other classes.

Rodriguez sits with them at the end of class and goes over social events at school so that they are not left out. She alerts them to the upcoming deadline for buying a yearbook, and makes sure they understand school announcements.

Perez and her mom are in constant contact. They text throughout the day on WhatsApp and see each other through video calls.

After two years, she will finally get to hug her again in July. She’s planning a trip to Mexico after graduation.

Her mom’s perennial question: “Are you sure you like it over there?” Followed by “Don’t you want to come back?”

But Perez knows what she wants.

“I want to keep going,” she said.

This is home again.

Have a news tip? Reporter Yadira Lopez: [email protected] or 541-473-3377.

For the latest news, follow the Enterprise on Facebook and Twitter.

SUBSCRIBE TO HELP PRODUCE VITAL REPORTING — For $5 a month, you get breaking news alerts, emailed newsletters and around-the-clock access to our stories. We depend on subscribers to pay for in-depth, accurate news produced by a professional and highly trained staff. Help us grow and get better with your subscription. Sign up HERE.