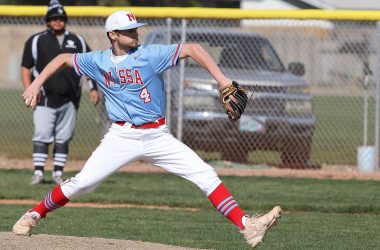

Juan Carlos Gonzalez is the first Hispanic elected to Metro’s council in Portland. (Portland Tribune/Jaime Valdez)

Juan Carlos Gonzalez was a high school junior from Forest Grove when he encountered President Barack Obama in Washington, D.C., through the Boys Nation leadership program.

Meeting the nation’s first black president made a lasting impression on Gonzalez, the son of Mexican immigrants.

“His campaign slogan was hope. He just activated so many people in the country to think about the United States in the way that he did,” Gonzalez said. “He was larger than life. I thought if he could be the first, I could be first in something else. Glass ceilings could be shattered.”

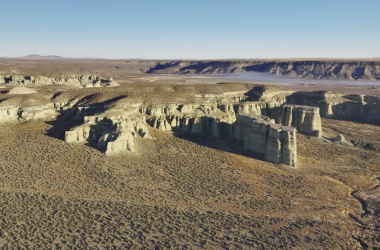

Gonzalez, 26, director of development and communication at nonprofit Centro Cultural, recently won election to Metro, the Portland area’s influential regional planning council. The agency is responsible for planning infrastructure and development across jurisdictional boundaries and protecting green space.

When he takes office in January, he will be the first Hispanic to serve on the council and possibly the youngest member in history. Metro officials confirmed he’s younger than any of the 22 councilors who’ve served since the elected body was reorganized in 1995.)

Oregon has seen a surge in recent years in Hispanics seeking and winning election to public office, from local school boards to the Oregon Legislature. According to the U.S. Census, Oregon had about 495,000 Latinos in 2017 – 13 percent of the state’s population. That’s up from 11 percent in 2000.

The recent election advanced that trend with Gonzalez’s win and the possible election of Eddy Morales to the Gresham City Council. Multnomah County is recounting the votes in Morales’ race against incumbent Kirk French because the margin was so narrow.

Following the May 2017 election, the Woodburn School Board became a Hispanic majority, reflecting the makeup of its enrollment, and Latinx candidates continue to win seats on other school boards around the state.

School board members from Hispanic and other backgrounds formed the Oregon School Board Members of Color Caucus two years ago to increase their influence on the Oregon School Boards Association. During that period, the caucus has grown from a handful to dozens of members, said Erika Lopez, a Hilllsboro School Board member and part of the caucus.

The group is seeking a vote on the association’s board. A majority of school boards must agree, and some, such as Hillsboro, have already voted in favor, Lopez said. The caucus expects to find out the outcome by the end of the month, she said.

The movement to put Hispanics in office gained steam in 2014 after voters rejected an Oregon ballot measure that would have provided a four-year driving card to undocumented immigrants. Disappointment over the measure’s failure stirred Hispanic leaders to step up their advocacy and organizing, said Reyna Lopez, executive director of PCUN (Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste), Oregon’s union for farm workers and tree planters.

The same year, the Color Political Action Committee formed to find and support candidates who reflected their minority constituencies. Since then, other organizations with the same purpose have formed, including East County Rising in east Multnomah County.

President Trump’s immigration stands during his presidential campaign in 2016 helped galvanize unprecedented political organization in the Latinx community.

Lopez, a buyer for the city of Hillsboro, ran for office after her 10-year-old son came home from school and told her he was afraid she would be deported. Lopez, whose family emigrated from Mexico, is a citizen and can’t be deported.

But, Lopez said, the incident “was kind of the nexus of what was happening in the national policy landscape and … how it translates into our lives and in our communities.”

She said her son hearing “this negative narrative around people who look like me or come from where I come from. It was really disheartening.”

Even PCUN – which previously focused on working conditions – recently started recruiting Latinx candidates. Its political action arm, Accion Politica PCUNista, urged Teresa Alonso Leon, the daughter of a farm worker and the first in her family to graduate from college, to run for the House district that runs from Woodburn to Salem and helped buoy her to victory in 2016, Lopez said. Leon, then an administrator at the state Higher Education Coordinating Commission, was the first Latina to serve in the Legislature.

That same year, the Legislature gained two other Hispanic lawmakers – Diego Hernandez of east Portland and Mark Meek, a real estate broker from Clackamas County.

Hernandez, co-founder of Momentum Alliance, a youth-based nonprofit that developes young social justice leaders, was the first Latino to serve on the Reynolds School Board and is the youngest member of the Legislature.

Lopez was elected to the Hillsboro School Board in 2017 after participating in Emerge training, a nonprofit that recruits and trains Democratic women for office. She learned how to file campaign finance reports, land endorsements and build up a resume before running for office.

The Hillsboro School District, where 37 percent of students are Latinx, had no Hispanic board members at the time. The board appointed another Latina, Yadira Martinez, a dental hygienist, earlier this year.

Martinez, raised in Hillsboro, said she sought the appointment because she realized the Hispanic community needed more involvement and “our voices need to be heard.”

To win votes from Hispanic voters, advocates do a lot of canvassing. PCUN sent out Spanish-speaking employees and volunteers for house calls, sometimes visiting several times to convince a voter to turn in a ballot or help them understand the ballot choices, Reyna Lopez said.

Many of the Latinx office holders are what Lopez dubs the “Mexi-lennials.” They are children of undocumented immigrants to whom Congress granted amnesty through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Often referred to as the “Reagan Amnesty,” the act legalized undocumented immigrants who had entered the United States before 1982, had no criminal record and could pass a citizenship test.

Mexi-lennials’ parents often came to Oregon without proficient English skills or a high school diploma and weren’t active in politics.

“They are shy about exercising their rights,” said Lopez, 31. “The new generation doesn’t feel that way. We went to the public school system, and many of us went to college. A lot of us are able to vote, and we have a different perspective on what our rights are.”

When Lopez was 9, her mother received her citizenship through the Reagan Amnesty. As a child, Lopez acted as a translator for her Spanish-speaking mother, including at a medical appointment.

“In the Latinx community, it is a big deal to turn 18 because ever since we were very young, we have taken on a lot of responsibility for our family,” Lopez said.

“Especially now, because we are aware of the issues, we care about immigrant health care, our businesses and the ability to retire,” she said. “The only way you can make a difference and have a voice in the things that happen around you is to vote” or run for office.

Morales said growing up in an immigrant family gave him empathy and focus on solving issues that face disadvantaged residents.

“I lived with a single mom so we moved around every two years, which I think is very common for a lot of people,” Morales said. His mother became a citizen under the 1986 amnesty.

Morales said he attended four elementary schools, three middles schools, and two high schools – Marshall High in east Multnomah County and Sherwood.

“We would move to places where she could find work and find housing that was affordable,” Morales said. “Growing up in that situation and in a bicultural way helped me to be very adaptable and helped me to understand some of things I ran on like housing security.”

He was the first in his family to graduate from high school, go to college, own a home and seek public office.

“I think that is probably the case for a lot of Latinos — to be the first,” he said. “It shapes the way that we live. We take the time to listen and learn. We look for collaboration, but we also bring a really unique set of experiences that allow us to understand there are more people like us out there who have not had access, and we end up championing a lot of those issues.”

His campaign reached out to new voters, translating materials into Spanish and other languages and spending time explaining to voters the mechanics of voting.

“This idea to being new to the political system and the political process was something I could relate to. I won votes in all parts of Gresham and among all demographics,” Morales said. “The thing that made our campaign unique is we understood what it was like to be a new voter. We spent a lot of time educating citizens who had never voted before.”

“The recent election of members of Congress who come from more diverse backgrounds show that voters are willing to embrace all kinds of leadership,” Gonzalez said. “As we start building support and an apparatus for candidates to feel supported with organizations like Emerge and we have trailblazers who are willing to lend their name like Rep. Hernandez and use his political momentum for other candidates, we will continue to activate many other leaders to run for office.”

But the Hispanic community still has a long way to go to make it voice heard, Lopez said.

“I will feel we have gotten to that place once any one of my cousins has voted without me having to nag them about it,” she said. “I think in places where we have made efforts to engage civically, I think we are seeing that making a difference but not every place is like Woodburn.”

UPDATE Nov. 26 — The story has been amended to reflect the full name of the school board caucus.

UPDATE Nov. 30 — The story has been corrected to reflect that Juan Carlos Gonzalez was the first Hispanic elected to the Metro council. A Hispanic earlier had been appointed to the council.

Paris Achen: [email protected] or 503-363-0888. Achen is a reporter for the Portland Tribune working for the Oregon Capital Bureau, a collaboration of EO Media Group, Pamplin Media Group and Salem Reporter.